The Game

Lisboa is one of the most popular games from the well-known Portuguese designer Vital Lacerda. It is a heavy Eurogame about the rebuilding of Lisbon after the major earthquake in 1755, which triggered a tsunami and also led to a great fire that ravaged the city for three days.

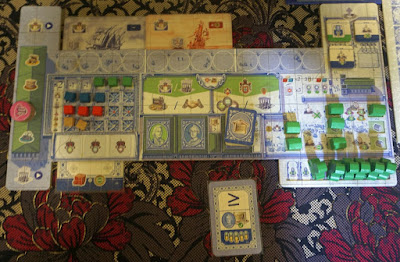

The game board is huge and contains a lot of information. The right half mainly features the four streets of Lisbon. This is where you will build shops and public facilities. The left half features the three important nobles - the builder, the minister and the king. Actions you can take when visiting them are shown on the game board.

The game is played in two halves. You have a hand of 5 cards. On your turn you play a card to perform some actions, and then you draw a card from one of the four draw decks. The decks are face-up so your opponents know what card you are picking. Three of the four decks are related to the three nobles. When an opponent picks a card related to a particular noble, chances are he intends to take actions related to that noble. The fourth deck is an event deck and these cards have various powers. One half of the game ends when three decks run out. Player choices when drawing cards affect how quickly the game progresses. Another way a half ends is when a player collects a specific combination of rubble. In this game, rubble from the earthquake can be reused for the rebuilding efforts.

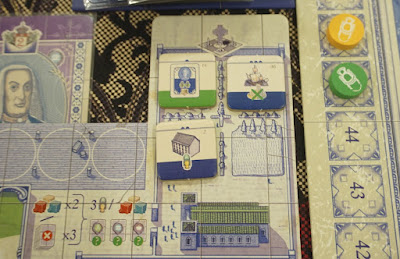

This is the player board. When you play a card, you play it on the main board or on your player board. If played on the main board, you will visit one of the nobles or trigger an event. If played on your player board, you improve your abilities. The indents along the top and bottom of your player board are for you to tuck cards. You can tuck up to 3 cards horizontally from the top, and up to 3 cards vertically from the bottom.

The most common action type in the game is probably visiting a noble, which requires playing a card on the main board. When you perform this action, other players may follow. They can spend a favour token to join you in visiting that same noble. As the active player you perform two actions related to the noble. Others piggybacking on your visit get to perform one.

The icons at the top and bottom of the cards are what will be showing when you tuck cards below your player board. These icons will be the permanent benefits you gain after you play a card at your player board.

This is the area where you do the actual rebuilding of Lisbon. There are four streets (the coloured stripes) and five rows of shops (well, technically the five rows of empty spaces where you can build shops). Along the north, east and west edges there are spaces for public buildings. When you build a shop, you place a shop tile next to one of the streets. Every shop tile has a little opening which represents the front door. When you place your shop, the street the door faces determines which kind of goods your shop produces. Of the five rows where you can build shops, when you build in the centre three rows, you always have two options. If you build in the first or last row, the door can only face one specific street - the yellow or the blue.

Those red, blue and natural cubes are rubble. When you build a shop, the cost is determined by rubble in the row and column of the shop. In the early game building shops is expensive. It gets cheaper gradually because every time you build a shop, you will remove (and reuse) a rubble cube. You want to collect sets of rubble (a set is three colours). It improves your abilities, e.g. your warehouse capacity.

These on the right are public buildings. To construct them you need to have obtained plans from one of these two architects, Mr Blue or Mr Green (sorry I don't remember their names). You don't need to spend cash, but you have to spend people (officials). That's essentially another currency.

Below each of the three nobles you can see three different actions. When you visit a noble, you must perform the main action, and you may perform one of the two secondary actions. The main actions are building a shop, claiming a decree and constructing a public building. Decrees are cards which score points for you at game end, if you fulfil the conditions specified.

The secondary actions are claiming two officials, taking an architect's plan, buying a ship, producing goods, moving the cardinal and taking a favour token. You produce goods to be sold for cash or to barter actions from the nobles. Goods are produced at shops, so you need to build shops before you can produce anything. Selling goods for cash requires ships, but you can use other players' ships, just that they will gain points for shipping those goods.

Here are some decree cards. Wigs in Lisboa mean victory points. Most decrees here score 5VP if you have the most of something. The decree in the centre scores 2VP for every public building designed by Mr Green Architect on the west side of the city.

That pawn at the top left is the cardinal. He moves around this track. Whenever you move him, you can claim one of the clergy tiles next to where he stops. Clergy tiles give you various abilities and bonuses. You can also discard them for points.

The four goods are worth between $4 and $6 at the start of the game. Selling goods by shipping them off is one way to make money. Every time anyone produces goods, the prices drop. Goods will be worth less and less as the game progresses. However in the later game you will produce more and also you will be able to ship more. That offsets things somewhat.

When you claim clergy tiles, you have to place them in this corner of your player board. There are only four slots. When this gets full you will have to discard clergy tiles.

The artwork and graphic design is done well. I love the attention to detail.

The Play

Lisboa is a typical heavy point-scoring Eurogame. There are many ways you score points. You'll do scoring during the game, and you'll also do a bunch of scoring at game end. In our game, almost half of the final scores came from game-end scoring. The main thing you do in the game is you build shops and public buildings. Making money, claiming architectural plans, recruiting officials are all things you need to do in order to build stuff. Producing goods, buying ships and shipping goods is one other major process flow, and you do that mainly to make money. That brings you back to using the money to build shops.

During play you must remember to claim decrees. This is basically positioning yourself for the end-game scoring. You claim decrees sometimes not just for yourself. You may also claim some for the sake of denying your opponent. As players collect different types of decrees, they priorities diverge. They will tend to focus on fulfilling the criteria on their respective decrees.

Cards, decrees and clergy tiles come in a huge variety. Every player gets a booklet listing all of them and their powers. When we played we had to refer to the booklet all the time. Learning this game takes a fair bit of effort.

On your turn, the broad stroke is you play a card then pick a card. Where you play that card determines what actions you perform. The basic actions are those 9 printed on the board, plus selling goods, for a total of 10. None of these are particularly complicated. However many of them are related to other rules and mechanisms, like how to calculate the cost of an action, whether your opponents get to follow, what the restrictions are. There is a lot to digest.

There is plenty of player interaction. You fight over building lots on the map, both for shops and public buildings. It's first come first served. You station your officials at the offices of the three nobles, to make it more costly for your opponents to visit them (aah bureaucrats). You also fight over decrees. With decrees which reward points for being top in certain criteria, you can deny your opponents the points even if you don't claim the decree. You just need to do better than them in those criteria.

At this point I had two ships tucked along the top of my player board. I had one card tucked at the bottom, and it makes red rubble cheaper by $1, i.e. being discounted from $2 to $1. Those little houses at the bottom right are used for marking shop ownership on the main board whenever you build a shop. When you remove houses from your player board, you unlock new abilities too.

Whenever you build a shop, you claim one rubble cube. If you build a public building, you claim two. Whether you are building a shop or a public building, you will gain a one-time benefit as specified on the space of the building.

A shop may earn victory points up to three times, if it matches up with the right type of public buildings. When you build a public building, it may help your opponents' shops earn points.

We did a 3-player game - Han, Allen and I. Han had played before, so he taught us the game. Our scores were close throughout most of the game. However when we did the final scoring, Han's score sprinted ahead and he won by a large margin. He had more shops than us.

The Thoughts

I have come to a realisation, or perhaps I should say I am finally admitting it to myself, that I'm drifting away from heavy Eurogames. For many years I have identified as a hardcore gamer primarily playing heavy strategy games, and I am solidly in the heavy Eurogame camp. In recent years, I find myself less and less patient with these games. Games which spark my interest are no longer games in this genre. I think the problem is there is less innovation in games of this genre. But I may be wrong. Maybe the problem is with me. Maybe my taste has changed.

I find Lisboa tiresome. Sorry to all the fans, and I know it has many. It's not bad, just that for me the effort I have to put in is higher than the enjoyment I get out of it. It has many rules and mechanisms, and I don't think all of them are necessary. I would enjoy it more if it were more streamlined. But perhaps it would not be what it is were it streamlined. If someone else at a table is keen to play, I'll probably agree. Now that I know the game, it will go more smoothly.

I'm pretty sure this is a story-first-mechanism-later game. Many important elements in history are retained. If this game were a mechanism-first game, I'm pretty sure it would be less complicated. Which comes first, story or mechanism, doesn't decide whether a game is good or bad. The story is a big part of many games. It is part of the play experience that the designer creates for the players.

No comments:

Post a Comment