The Game

Horseless Carriage (2023) is the latest game from Splotter. I am a big fan of their games, and by now I have reached the stage I can confidently buy-before-try. They are the only game designer team I can say that for. Their previous title was Food Chain Magnate (2015), which was 8 years ago. These guys take their time.

Horseless Carriage is about the early days of the automobile industry. Cars are a new product on the market. As car manufacturers, you need to work out what exactly your customers want, so that you can develop the right products. At the same time, you are also shaping what the market perceives to be important features. Car buyers are fickle, and tastes regularly change. You need to be able to handle the ever increasing customer expectations while at the same time competing with your opponents to sell cars. The richest player at the end of the game wins.

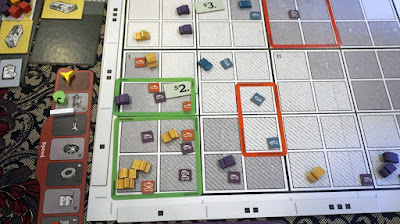

The most important part of the game board is the 8x8 grid on the left. This represents the car market in an abstract way. The X and Y axes represent two different types of requirements of car buyers, e.g. safety, speed and range. Buyers at the lower left corner have no expectations, while those at the top right corner expect many features to be available in your cars. Naturally those who have high expectations are also willing to pay more.

The rest of the board are various tracks, including for turn order, scores and production capacities.

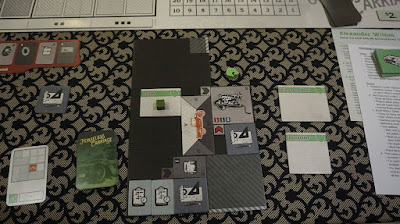

You have your own player board, which is your car factory. This is the most important part of the game - how you place various tiles in your factory. I think of the player board as not just a factory. It is a representation of your car company. In addition to your production lines, you also place your dealerships, marketing departments, research departments and planning departments here.

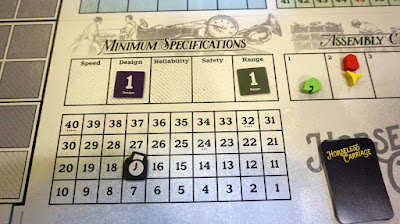

This is a countdown timer track. You play at most 7 rounds in a game. However some actions trigger this timer. If the timer hits zero before you complete 7 rounds, the game ends early. If the game ending early is beneficial to you, you can deliberately manipulate the timer. This also means sometimes you need to think twice before performing certain actions, because your action may cause the game to end earlier than you prefer.

Cars placed on the board represent buyers, i.e. market demand. Purple cars are regular cars (sedans), the golden ones are trucks, and the blue sports cars. There are black squares along the X and Y axes. They represent how many features of a specific category that the buyer expects to see in your car. For example the Y axis is currently associated with safety features (light brown). Near the top left there is a truck in the row marked with two black squares. This means this particular buyer who is looking to buy a truck wants a truck with at least two safety features.

These frames represent the reach of your dealerships. The more marketing departments you have attached to a dealership, the bigger the frame you can use. Bigger frames let you reach out to more customer segments.

When selling cars, you place the frames on the board like this. Your dealership must fulfill the requirements of customers in all segments covered by the frame. When players' frames overlap, it means they will be competing for the same customers. Turn order for selling cars becomes crucial.

This is a factory, i.e. player board. The tiles with cars are the mainlines. They are the hubs for producing cars. They must be connected to dealerships - those white tiles with cubes. Cubes on dealerships represent how many features and in what types the cars sold here have. The four sides of a mainline are in white and three different shades of grey. These four sides allow the mainline to be connected to up to four separate assembly lines, which I'll call sublines. Let's take the orange truck mainline as an example. On the A (white) subline, there is a workstation producing doors. All tiles in the A subline must have the same white background and must be eventually connected back to the A side of the mainline. There is a purple arrow pointing at the door workstation. This indicates that the workstation is producing a purple, i.e. design, feature. This allows you to place a purple cube on the connected dealership.

On the B subline (light grey) there are two workstations. The interesting one is on the right. It has two arrows pointing at it, green and red. This means it is producing two features, a green range feature and a red speed feature. These allow the green and red cubes to be placed on the dealership. Notice that this B subline is at the same time serving the other mainline making purple sedans. If you can get separate mainlines to share some sublines, you will save much space and heartache.

My truck mainline has no D (dark grey) subline, because I have no space for it. I have no option to use any dark grey workstations. Tiles once placed on your factory floor can never be removed or shifted. This is very much a Splotter design philosophy. You have to plan carefully and know what you are doing. An early mistake can ruin your game.

You will place more are more cubes on your dealerships, meaning your cars will support more and more features, in order to meet customer expectations.

These are the tech tracks. There are five of them in total. Two will be placed next to the main board, to represent the two types of features buyers want most this round. The other three which are off board are still important and you need to pay attention to them. At the end of every round, one of the tech tracks at the main board will be replaced with one of these three off board. What buyers expect will change every round. The white bars on the three off board tech tracks represent the minimum requirements of the market. You must fulfil all minimum requirements to be able to sell your cars, and not just those two types on the main board.

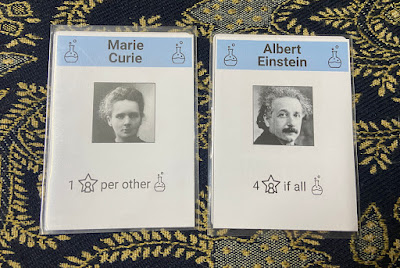

The player markers on the tech tracks represent your research level. Research level grants you access to specific workstations as shown on the tech tracks. One important rule is if your turn order is ahead of other players, you can use their techs as if you own them. This is called using their patents. It is difficult to develop all techs by yourself, so turn order is an important element to pay attention to.

Players' research levels influence which types of features will be demanded by buyers. The more you research a tech, the more it will get prioritised to be moved to the main board next. If you want to manipulate which tech goes next and which doesn't, this is how.

Every round you get to develop new market segments. By doing this you generate regular new demand on the main board. This particular card will create demand for four sedan cars from now until the end of the game.

When you develop new demand, you place those tiny square tiles. Every round these square tiles generate new customers (i.e. car pieces). This is predictable and you can plan how you want to compete and which customers you want to serve.

The Play

Horseless Carriage is a 3 to 5 player game. Han, Allen and I did a 3-player game. We were all new to the game. My gut feeling is it will be more interesting with more players, because competition will be more intense.

Han and I had read the rules, and we both agreed that it was hard to imagine how the game worked. The rules were not that complicated. As veteran gamers, normally by reading the rulebook we can more or less figure out how a game works and what the general strategies will be. With Horseless Carriage, we felt lost and had little idea what we should be doing. It feels like having read a sentence, and despite knowing every word in it, I still don't understand what that sentence means. We had to sit down to play to start learning how the game actually works.

The core of the game is laying tiles in your factory. It's all about planning. You start with a large factory floor. Every round after placing as many tiles as you want, you get to expand your factory floor in preparation for the next round. You will be doing this six times. By the seventh round when the expansion tiles run out, it is time for the game to end. All those tiles you get to place on your factory floor are free! The mainlines, the workstations, the dealerships, the planning departs. All free. If this game were designed by someone else, each department and function may have a different cost, and you have to make money and save up to buy them. In the end it becomes complexity for the sake of complexity. In Horseless Carriage, the designers had decided that these aspects were not the core of the game, and did away with them. I admire that.

Every tile on your factory floor, once placed, can never be removed or shifted. This is very much in the spirit of other Splotter games. You'd better know what you're doing. This is not the kind of game that you can happily do random things and explore at your leisure and expect to be able to steadily work things out and catch up by game end. This is an unforgiving game. An early and bad mistake can doom you for the rest of the game. This is the kind of game that Splotter makes. They don't give you child guards. No catch-up mechanisms. No protection from doing stupid things. If you are going to play a Splotter game, you have to remind yourself you are an adult now and you will take responsibility of your own actions.

By Round 2, Han, Allen and I were already stunned staring at our factory floors and repeating oh crap oh crap oh crap in our minds. Mistakes in the first round already started haunting us. It was like having dropped a pound of salt into the broth and now we had to think how to save the mess. It was disaster management. We needed to work out how to not further screw ourselves. It was funny to have three grown men brooding over a table muttering what am I doing.

The ever increasing customer expectations are a constant source of pressure. We needed to plan ahead and predict what the market would want, and then design our factories accordingly. We had to allocate space for workstations which would help us fulfil customer expectations. There were five different types of requirements, and customer priorities changed every round. It was challenging to keep up. This is a game about long-term planning. While working towards meeting market expectations, we were also competing among ourselves.

We didn't compete too directly in the factory building aspect. We couldn't mess with one another's factories. However the quantities of the workstations were limited. If one particular type ran out, it would be bad news for anyone who still needed that type. We still needed to watch closely how others were designing their factories, so that we could plan how to compete on the main board. You gotta know your enemies.

More direct competition came from selling cars. If our car features were about the same, we would be competing for the same customers. Players have some control over generating market demand. If you know there are certain expectations which only you can meet and no one else, you'd want to create such customers. You would monopolise that segment. With three players, the game board felt rather spacious. However we often couldn't serve many of the customers. So maybe the game does need that big a board. Or maybe we were just horrible at playing.

I was the only person making trucks (the golden pieces). I thought having a monopoly would mean big bucks coming in all the time, but that didn't exactly happen. Most of the time I didn't manage to produce trucks with many of the desired features, so I mostly sold to low-end customers who had little or no expectations. I only had myself to blame. Allen and Had did consider competing with me, but the truck mainline was a large piece, and they already had enough trouble managing their factory floors. They didn't want another major project to have migraine over.

Being able to expand assembly lines from the mainline tiles is of utmost importance. This is how you keep up with customer expectations. Ideally you want to keep your options open for all four sublines A, B, C and D, but that's difficult to do. This is very much a spatial game. If you are producing two types of cars, it is best if they can share some sublines and workstations. That's going to save you a lot of pain.

We only played 5 rounds. By then, the result was clear. Han produced sports cars, and he managed to create a group of high-end buyers which only he managed to sell to. His sports cars had many features and round after round he focused on selling expensive toys to these rich boys. Sports cars themselves were already more profitable than regular cars. Being able to serve the high requirement segment meant even more profit for Han. Allen's sports cars couldn't compete, and I didn't make sports cars at all. By Round 5 we knew it was impossible to catch up to Han.

The Thoughts

Horseless Carriage did not disappoint. It is a heavy Euro strategy game, very much in the Splotter style. This is the kind of game hardcore gamers like. I like that the game doesn't rely on too many rules or too complicated rules to create a rich and interesting strategy space. It is not minimalistic. It uses just enough to make the game work. Some simple and seemingly innocent rules have much tactical consideration behind them. No doubt this is a heavy game, so it is not for players new to the hobby.

Designing and expanding your factory is a spatial challenge. It is the bulk of the game. It reminds me of Uwe Rosenberg's polyomino games. That's essentially what you're doing right? But here the gameplay is much more complicated. It is not just about filling spaces and leaving as few holes as possible. There is much more you need to consider. Horseless Carriage also reminds me of Martin Wallace's Automobile. They share the same setting. The mechanisms are vastly different. Automobile is less complex, but not by any means a light game. I like them both. Horseless Carriage made me itch to play Automobile again.

Some of the earlier Splotter games like Antiquity and Indonesia get complaints about being fiddly. Indeed they have some components which are tedious to manage during play. I am not too bothered, as the enjoyment is worth the trouble. The fiddly part of Horseless Carriage would be those flimsy plastic frames. When we played, if we could tell apart our dealership ranges easily, we didn't bother to place the frames. Only when we had overlaps, and thus direct competition, then we used those frames. They are still a useful visual tool, just a bit difficult to handle.

I thought about whether Horseless Carriage has enough player interaction. You can't mess with your opponents' factories, so that part of the game, which is the most important part, feels a little like multiplayer solitaire. In our game, Han cornered the billionaires sports car market, and there was squat Allen and I could do. Eventually I concluded that there is plenty of player interaction. You do have to be acutely aware of what your opponents are doing, and you have to think about what they are planning to do. You have to decide where to compete and where to concede. In our game, there were parts I felt helpless about, but it wasn't due to a lack of player interaction. I had already missed the opportunities to do something well before I got to the helpless situation. Horseless Carriage can be a brutal game, and I love that. It has both a rich strategic layer and a complex execution layer. You can't neglect either one. I like how important the strategic layer is. If you fare poorly at that level, no amount of good execution will save you.

This is the way.