I shall continue to write about games I tried at the Asian Board Games Festival (Malaysia) in Penang. This time I will write about games from Taiwan and the Philippines. Drama Job Hunting is a party game from Taiwan. It is the fourth and latest game from the Drama series. It is the simplest version to date. It can be used as a children's game and for education purposes.

If this game were to be translated to English, I think an apt name would be Drama Queen.

Let me talk about the core idea in the series. Every round an options card is drawn and shown to all players. The card lists six items. One player will be the actor for the round. The actor draws a number card which will show a number between 1 to 6. Only he gets to see this. He must then act out the item under this number on the options card. He can't speak or use sound effects. He can only use gestures and facial expressions. The other players all try to guess the correct answer. After everyone has made a guess, the correct answer is revealed. Whoever gets it wrong is penalised. However if everyone gets it wrong, then the problem is the actor. The actor is penalised instead. You can decide up front what the penalty should be. So yes, this can be a drinking game. If you are not playing with children.

In Drama Job Hunting, the possible answers are all occupations. This sounds easy but on some cards the occupations are similar, for example taxi driver, ambulance driver and bus driver. Generally this is easier than the other versions. This might not be very interesting for seasoned gamers. I find the other versions more enticing.

Drama Bar is different in that you can't use gestures of facial expressions. You can only use your voice. The options card shows a specific phrase you must say. The list of six items are the possible situations in which you say this particular phrase. Let's use the example below to better illustrate this.

The phrase you have to say here is simply "Sorry". The 6 different situations are:

- Accidentally touching someone on the bus.

- Being late.

- Your girlfriend forces you to apologise.

- Your phone rings when you are at the library.

- You forget the person's name.

- You are asking a person to let you pass through.

How are you going to express these different situations by simply saying "sorry"? Not so simple eh?

This one is "What time is it?" The possibilities:

- Mom who is cooking in the kitchen saying this to Dad who is in the living room.

- Your friend is late by one hour.

- Your employee is late by one hour.

- You are asking a passer by the time.

- You have overslept and you are panicking, asking the person lying next to you.

- You just remember that there is a show you want to catch.

When playing Drama Bar, you have to cover your face, so you won't be able to express yourself using your facial expression. This can be quite challenging indeed. So far this is my favourite among them all.

I am guessing Drama Oscar is the first in the series. You need to act out an emotion, and that emotion can be caused by very different things.

The emotion here is being secretly thrilled or tickled. The possible reasons are:

- You see your headmaster slip and fall.

- You are a young and innocent lady and someone has just confessed their love to you.

- You overhear a conversation and they are saying how handsome you are.

- You are the top student and you see that you are top of the class yet again.

- At the Oscars the host announce that you win the best actress award.

- You hear on the radio that the Taiwanese baseball team has defeated the Korean team in a comeback victory. (context: this is a game from Taiwan)

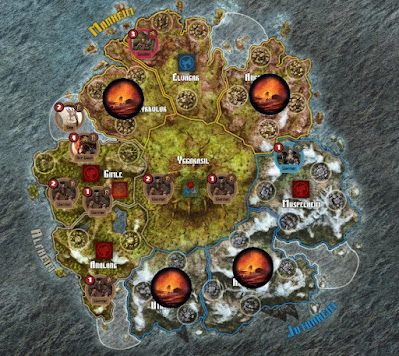

Drama Arena is about kung fu moves and spellcasting. This is a version which gives you plenty of opportunities to be creative.

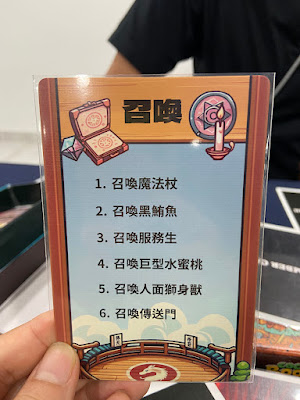

You can even get two actors to perform at the same time, and they can fight each other. This one above is about casting a summoning spell. The possibilities:

- Summon the magical staff.

- Summon the black tuna.

- Summon the waiter.

- Summon the giant peach. (I'm not sure whether this has any naughty connotation)

- Summon the Sphinx.

- Summon a portal.

This card is for water magic.

- Dragon Shot.

- Dragon Spiral.

- Waterfall Attack.

- Water Storm.

- Rain Arrows.

- Water Cannon.

The

Drama series is doing well in Taiwan, and they have four different versions now.

Tom is interested to bring it beyond Taiwan. To do this in other regions and languages, a lot of localisation work will be required. If any publisher out there is interested, get in touch with him.

Watchlist is a game from the Philippines. It is a real-time cooperative game that can be played in five minutes. One player is the undercover cop while the rest are regular cops. The undercover cop needs to help his team arrest all the suspects.

There are two sets of cards in the game and they are almost exactly the same. The only difference is one deck is in colour, and the other is black and white. The undercover cop gets the black and white deck, and the regular cops get the colour deck. At the start of the game, the undercover cop draws a certain number of cards from his deck. These are the suspects he must help his team arrest. The colour cards are distributed evenly to all the other players. The process in the game is everyone asking questions to the undercover cop to identify the current suspect. The undercover cop can only answer yes or no. You ask questions like whether the suspect is male or female, whether they are wearing a hat, whether they are holding something in their hand, and so on. One of the regular cops makes a guess by playing one of his cards. Only correct guesses will score points.

Since this is a real-time game, the undercover cop will get bombarded with questions from all the other players. Whether the cards are coloured or black and white doesn't seem like a big deal, but this does pose a challenge. Some things in the drawings may be interpreted differently when there is no colour.

Folded Wishes is a game that has gone beyond the Philippines and has reached the international market. Ludus is the original publisher, and B&B Games is the international publisher.

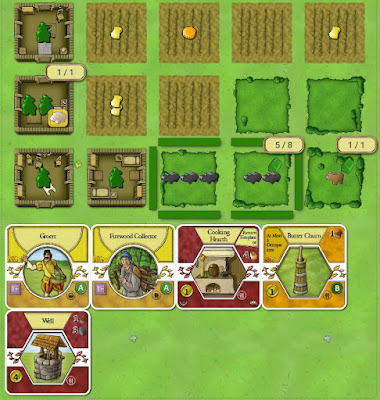

Folded Wishes is an open information abstract game. Your goal is to arrange four of your pieces in a straight line. You will always have one tile in hand, and on your turn you will play this tile at one position along the edges of the play area. You place your game piece on this tile. You then push the tile into the play area, shifting that whole row of tiles. One tile will get pushed out from the other end of the play area. You'll pick this tile up for your next turn.

All the tiles have small icons and these are special powers you get to use. Some let you move your game piece, some let you move an opponent's piece, and some even let you swap your piece with an opponent's.

You can complete missions to earn additional powers. Missions come in the form of having your pieces arranged in specific patterns. When you earn a new power, the new power is linked to tiles in specific colours. You can only use these powers when you play a tile in that particular colour.

The game is chess-like, because this is a perfect information game. There are many tactics and strategies to explore.