Plays: 3Px1.

The Game

Stephenson's Rocket is an older game from Reiner Knizia. It was first published in 1999, and has been out of print for many years. A new edition was released in 2018, and because of that I had the opportunity to try this highly praised game. In the second edition, there were only small changes to the rules. The game components underwent a bigger upgrade.

The train sculptures are nice.

This is the game board. This is a map of England. There are cities (dark brown), towns (light brown) and starting towns (in the colours of the railroad companies). There are 7 railroad companies on the board, and their trains start on their respective starting towns. The upper left section is the city investment chart, which records who has invested in what factories at each city. The lower left section is the share tracks, indicating the shareholding status at each company.

In this game you invest in and manage railroad companies. By holding shares in the companies and by owning train stations, you score points for the achievements of the railroad companies. To develop a company is to move the train and extend its tracks. When one company's train tracks meets those of another, these two companies merge. As the game progresses, the number of companies dwindle, and when there is only one big train network left, the game ends.

On your turn you have two actions, and there are only 3 options to pick from. You may mix and match in any way you like, except you can't develop the same company twice on the same turn. Let's talk about developing a company. What you do is simply move a train one step forward, to one of the three spaces in front of it. It cannot move backwards. On the space the train has just left, you lay a train track, thus extending the railway line. Imagine a snail slithering forward and leaving behind a trail of slime. The train in this photo has moved 3 times. I started on the orange starting town. The first move was towards the northeast. The second move too, and that connected the railroad to Guildford, a city. The third move was towards the north, and this connected the railroad to another city - Reading. That brown building is a train station, built by a player.

Whenever you develop a company, you gain one of its shares. This is how you get yourself a stake in the company. When you move the train, any other shareholder may call for a veto and suggest a different direction to take the company (pun!). A bidding process ensues to determine where the train will go. The bidding is done using shares you hold, and shares are precious. So vetos are not to be taken lightly.

The second type of action is to build a station. In this photo I (white) had built one of my stations. Stations must be built on clear land and must not touch any train when being placed. When this particular station was built, the yellow train was still on its starting town. I had hoped that when this train company was developed, the train would come to my station. Unfortunately things did not work out the way I wanted.

Stations help you score points. Every time a railroad company reaches a new town, scoring is done based on the number of cities, towns and starting towns it is connected to. The player with the most stations in the railroad network scores full points. The player with the second most scores half that. If a company visits many towns, this scoring will be done many times. Also when companies merge, they become more and more lucrative because they will have more and more cities, towns and starting towns.

When being built, a station is at least two steps away from the nearest train. That means you need foresight and forward planning. After you build your station, you need to try to guide the train to it. Else your station is wasted. The need for a train to go or to not go in a certain direction is why the veto mechanism exists. Another important mechanism is the passenger mechanism. If you drive a train to an opponent's station, you earn one passenger. At game end, whoever has the most passengers gains 6VP. Second place gains 3VP. Passengers create an incentive to help your opponents.

Now the third action type - investing in industry. You build a factory in a city by placing one of your cubes onto an empty space on the city investment chart. Each row on the chart represents one city on the board. Each city has three slots. The factories you may build are of four industry types. At game end, each industry is examined. Whoever has the most factories gains 6VP. Second most gains 3VP. There is one condition. If a city is not connected to any railroad, its factories are discarded and do not count. The black cubes on the city investment chart remind you which cities have been connected to railroads.

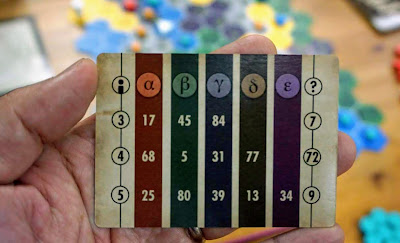

This is the player board. Those at the top left are the stations. The icons remind you where you can and cannot place stations. Those two in the centre are passengers collected. The lower left section reminds you the scorings to be done in three situations: (1) when a railroad reaches a city, (2) when a railroad reaches a town, and (3) when a railroad company merges with another. The lower right section reminds you of the end game scorings. All these icons look intimidating, but once you understand the rules, they are very handy.

Let talk mergers. There are only 7 companies on the board, and thus at most 6 mergers per game. However these can be critical moments in the game. You must prepare well for them. When a train touches the track of another, it is acquired by the other train company and it ceases to exist. The biggest shareholder scores points based on how many cities, towns and starting towns the company has (before the merger). The second biggest shareholder scores half that. All shareholders then swap their shares for those of the new company, at a 2:1 ratio. The result of the merger is a bigger company with more cities, towns and starting towns. The new company will be more valuable. This is how escalation happens in the game.

I have mentioned several ways of scoring. The most important two are the mergers, which is based on shareholding, and connecting to towns, which is based on station ownership. Other ways of scoring are still important, but they are supplementary.

Understanding the rules doesn't help much in understanding how the game feels when in play. Let's talk about the play.

The Play

I did a 3-player game with Allen and Jeff. The game supports at most 4 players. I was white, Jeff was brown and Allen was blue.

In the early game only three companies were activated, the green company in the west, the dark blue company in the east, and the orange company in the south. At this point our station building was balanced, and trains tended to go to the stations, because of the lure of the passengers.

Jeff (brown) invested more effort in the dark blue company. He developed it more, so he became a clear majority shareholder. The seeds of disaster were sown even at this stage, just that Allen and I hadn't realised the danger.

The dark blue company grew bigger and bigger, becoming unstoppable. At this point the red company had started operations, and had also merged with the dark blue company. Jeff (brown) was in control of the dark blue company and diligently developed it. Allen (blue) and I (white) wanted a piece and jumped in. However this was probably not such a good idea. Although we gained shares, we could not catch up to Jeff, and we only helped grow the company even further, benefiting Jeff. Jeff (brown) not only was the biggest shareholder. He also had the most stations at the dark blue company. Allen (blue) wanted to compete with Jeff in the number of stations. He had now built a station near the dark blue train, hoping to bring the train to his station. The green and orange companies were in an awkward position, being neither here nor there, having fallen far behind the dark blue company.

Allen (blue) had built a station hoping to get it to become part of the orange railroad company. If this happened, all of us would have one station each, and nobody would have any advantage.

At the top left, the dark blue train had veered left and avoided Allen's (blue) station. Now the situation was Jeff (brown) and Allen (blue) both having two stations. The green train was heading towards the tracks of the blue train, so a merger was imminent. There were two white stations (mine) and one blue station (Allen's) in the green company. When the merger happened, Allen would have three stations in the merged company and become the player with the most stations.

The purple company in the northwest, the grey company in the north, and the yellow company in the southeast, were all still dormant.

The green company had now merged with the dark blue company. There was no more green train on the map. Every merger may create a major shift in shareholding positions. If some players hold many shares in the company being acquired, their old shares will be converted to a significant number of shares in the new company. This can shake things up. Since the share conversion rate is 2 to 1, you want to create mergers when your opponents are holding an odd number of shares, because this makes them waste that odd single share.

Whenever a company is acquired, you give it a big red cross in the share tracks section. The prestigious dark blue company was later acquired by another company - the purple company. On paper it was purple gobbling up dark blue, but in practice this was not the case. Jeff (brown) had many shares in the dark blue company. After the 2:1 share conversion, he became the biggest shareholder in the purple company. Same old same old.

The purple company started operations rather late, but it swallowed the four-in-one mega company and became the new giant. The dark blue company had triggered scoring many times when it was in operation, and Jeff was the biggest beneficiary. Allen and I knew it was nigh impossible to catch up. We tried to focus on different areas, competing with Jeff separately and trying to force him to fight two fronts. Not that it helped much. We should not have let things get to this point in the first place. We should have been more alert. In Stephenson's Rocket you need to think ahead and understand the implications of your actions and your opponents' actions. It is thoughtful and deliberate.

Allen (blue) had the most stations in the purple company now (four). I helped make this happen, because I'd rather him gain an advantage than Jeff. Can't have Jeff be number one everywhere, no? If you trace the path of the orange company, you will see it had avoided one of Jeff's stations (brown). Allen and I were desperate not to concede any more advantage to Jeff. We wanted to lose less horribly.

The grey company was now alive. I (white) had set up two stations, with the intention to get them to join the giant company.

Things went according to plan. The purple company was acquired by the grey company, and now I was the biggest station owner in the main train network - five stations.

At the end of the game, only one city had no railroad connections - Brighton on the southern coast. Any factories built there were forfeit. Among the four industries, I (white) won majority in the cloth industry (second column) and the brewery industry (fourth column).

My (white) final score was 42, Allen (blue) 51. Jeff (brown) was already far ahead of us, and still counting!

In this situation, the grey company had become an isolated company. A company being isolated means it can't trigger any merger, nor can it reach any new city, town or starting town. Isolated companies no longer give shares, so you can't fight for share majority anymore. To be more accurate, the game ends not when six companies have been acquired. It ends when six companies have been acquired or have become isolated.

The Thoughts

When I read the rules of Stephenson's Rocket, I thought it felt a lot like Acquire. Competing for shareholding is important, timing the mergers and reaping benefits from them is important. In Stephenson's Rocket there will be at most 6 mergers throughout a game. In Acquire there can be more. Stephenson's Rocket does not feel like a Reiner Knizia game to me. Many of his games are succinct and minimalistic. The ways of scoring are straightforward. The genius lies in the simplicity. Usually you can easily see where the twist is, and you will admire how clever it is. In Stephenson's Rocket, although you only have three options when you perform an action, these actions can have many long-term implications. When you move a train, you may trigger many other actions - the veto, and the various types of scoring. You need to understand the big picture and you need to understand the implications of every small action, and how they affect the strategic landscape. You need to think a little deeper. This is not a game I would recommend to people new to the hobby. Like Tigris and Euphrates, you need to know what you're doing in order to enjoy the game. It's not the kind of game you can muddle through half of, grasping the tactics along the way, and just enjoy the fun ride.

This is an open information game with no randomness. This is actually a little intimidating. Imagine Chess, and Go. They sound serious and unforgiving, and very much skill-based. Stephenson's Rocket is not exactly like those games, but it does share some of their features. How a game develops is solely based on the decisions of the players. There is no luck and no randomness. Skills matter. An experienced player is expected to defeat a novice. It is better to play this game with opponents of a similar skill level. If there is a gap in skill level, you probably should to play with open discussions and analysis to guide the less experienced players. Else they will likely get trounced by the veterans.

Having played Stephenson's Rocket, I feel I understand why it was not as popular as Reiner Knizia's other games of the same period. Games like Ra, Through the Desert and Modern Art had reprints much earlier and much more frequently, and didn't have to wait 19 years. Stephenson's Rocket is not a wide-appeal game like they are. It is not as straightforward, so it is not as immediately rewarding. It is a more deliberate game. Those who have learned to love it truly enjoy it, and that's why there had always been people asking for a reprint.

The green train looks good too. Unfortunately green is a company colour and not a player colour. I always prefer to play with green pieces. White is my second choice.